Reassessing relevance, rarity and prominence in 19th century popular American sheet music publications.

So little is known about 19th century music in this country by the average citizen. But popular music, the audible heartbeat of the new nation whose Constitution was ratified just 13 years before the beginning of the 19th century, has arguably defined the spirit and fabric of American personality more than any other art form.

Such a massive amount of scholarship has been focused on popular music of the 20th century yet the prior one hundred years, America’s first full century, has received proportionately little attention.

In those years we played. We sang. It was commonly what we did after dinner and off and on throughout the day. And the music for the songs was engraved on a sheet of rag paper with perhaps a lithographic cover, a picture on the title page that reflected what the song conjured or suggested. The pictorial illustrations that adorned the cover caught the eye in the music store and the attractive lithographic image looked smart on the piano.

But what value do these songs have for us now? What reflection of those years could be worth exploring? What about the music was alluring and what so important that it begs for study and conservation?

Let’s tackle the words relevance, rarity and prominence one at a time beginning with rarity.

Such a massive amount of scholarship has been focused on popular music of the 20th century yet the prior one hundred years, America’s first full century, has received proportionately little attention.

In those years we played. We sang. It was commonly what we did after dinner and off and on throughout the day. And the music for the songs was engraved on a sheet of rag paper with perhaps a lithographic cover, a picture on the title page that reflected what the song conjured or suggested. The pictorial illustrations that adorned the cover caught the eye in the music store and the attractive lithographic image looked smart on the piano.

But what value do these songs have for us now? What reflection of those years could be worth exploring? What about the music was alluring and what so important that it begs for study and conservation?

Let’s tackle the words relevance, rarity and prominence one at a time beginning with rarity.

|

c.1868-73 - Concanen litho, London, famous tale

|

1. Rarity

I define rarity by relating to ‘total copies extant’, both the number we know and, more importantly, the number we assume may be out there. Scarcity, often used in connection to ‘being somewhat rare’ is best viewed in terms of market conditions and being temporarily unavailable. The idea is, if you wait long enough you will find it. Many of the rarest sheet music publications from 150 to 200 years ago may be seen once in a lifetime and some not at all. |

First, here are a few examples from other fields:

In 1623, Shakespeare’s First Folio was brought to publication by John Heminges and Henry Condell. This was the first publication of the 36 plays by the great Bard then thought to represent the complete canon. There are perhaps 250 copies still extant of this initial publication, not all complete and many in a state of disrepair. Most all copies are in archives. They are very difficult to acquire. Rare?

In 1776 came the Declaration of Independence. There are maybe 26 or 27 known of the first printed edition, so in association, about ten times as rare as the First Folio, if you bought the number of 250 extant as being ‘rare’. It certainly is incredibly scarce as most all copies reside in public archives, the Folger Library holding 100 or more of the total number.

In 1814 Francis Scott Key wrote the Defense of Fort McHenry, which became the lyrics for The Star Spangled Banner, our National Anthem. This was published by Benjamin Carr in Baltimore, Maryland. There are apparently only 12 copies in existence of this first release, issued so rapidly and perhaps haphazardly that the subtitle was misspelled.

Meant to say Star Spangled Banner, a Patriotic Song, the ‘t’ was left out of patriotic and it simply read ‘Pariotic’. This misspelling is now a by-word among collectors of the SSB. If you see it on the page, you’re witnessing the principal point of first edition, gazing at a real rarity. The amended first edition is rarer than the ‘actual’ first. Which makes both issues rarer than 13th century editions of the Magna Carta.

Of course, there are many sheet music publications that are assumed to number less than 10, what I refer to as ‘single digit rarities’. There are just 5 copies known of Our Brutus, the lionizing song about John Wilkes Booth that was published post-assassination (likely by Blackmar in New Orleans) and sold on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C., just down from the Capitol.

There are cases where one copy of this or that is supposed to exist without a second yet found. A collector I know of has a music-title with a portrait of Mark Twain on the cover. A second is not known among veteran collectors. But if we wait long enough another may turn up.

Rarest of all, no copies are known to have survived of the first edition of The Liberty Song (1768) by John Dickinson, signer of the Declaration. This is the first patriotic song printed as a folio sheet music edition, published by Mein and Fleeming and advertised for sale at The London Book Store in Boston. It was included in Bickerstaff’s Almanac the following year.

In 1623, Shakespeare’s First Folio was brought to publication by John Heminges and Henry Condell. This was the first publication of the 36 plays by the great Bard then thought to represent the complete canon. There are perhaps 250 copies still extant of this initial publication, not all complete and many in a state of disrepair. Most all copies are in archives. They are very difficult to acquire. Rare?

In 1776 came the Declaration of Independence. There are maybe 26 or 27 known of the first printed edition, so in association, about ten times as rare as the First Folio, if you bought the number of 250 extant as being ‘rare’. It certainly is incredibly scarce as most all copies reside in public archives, the Folger Library holding 100 or more of the total number.

In 1814 Francis Scott Key wrote the Defense of Fort McHenry, which became the lyrics for The Star Spangled Banner, our National Anthem. This was published by Benjamin Carr in Baltimore, Maryland. There are apparently only 12 copies in existence of this first release, issued so rapidly and perhaps haphazardly that the subtitle was misspelled.

Meant to say Star Spangled Banner, a Patriotic Song, the ‘t’ was left out of patriotic and it simply read ‘Pariotic’. This misspelling is now a by-word among collectors of the SSB. If you see it on the page, you’re witnessing the principal point of first edition, gazing at a real rarity. The amended first edition is rarer than the ‘actual’ first. Which makes both issues rarer than 13th century editions of the Magna Carta.

Of course, there are many sheet music publications that are assumed to number less than 10, what I refer to as ‘single digit rarities’. There are just 5 copies known of Our Brutus, the lionizing song about John Wilkes Booth that was published post-assassination (likely by Blackmar in New Orleans) and sold on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington D.C., just down from the Capitol.

There are cases where one copy of this or that is supposed to exist without a second yet found. A collector I know of has a music-title with a portrait of Mark Twain on the cover. A second is not known among veteran collectors. But if we wait long enough another may turn up.

Rarest of all, no copies are known to have survived of the first edition of The Liberty Song (1768) by John Dickinson, signer of the Declaration. This is the first patriotic song printed as a folio sheet music edition, published by Mein and Fleeming and advertised for sale at The London Book Store in Boston. It was included in Bickerstaff’s Almanac the following year.

|

2. Relevance

Both relevance and prominence are linked in multiple ways. Without question, historical and social relevance has become the #1 focus in 19th century American popular sheet music collecting and in determining the need for archival preservation. Absolutely, beautifully illustrated title pages can be the most alluring attribute for certain publications. However, there are a great many printings, especially from the first half of the 19th century, that have no pictorial cover at all. Overall, it is widely accepted that the primary linkage to historical documents is through historical relevance rather than artistic merit or worthy composition. |

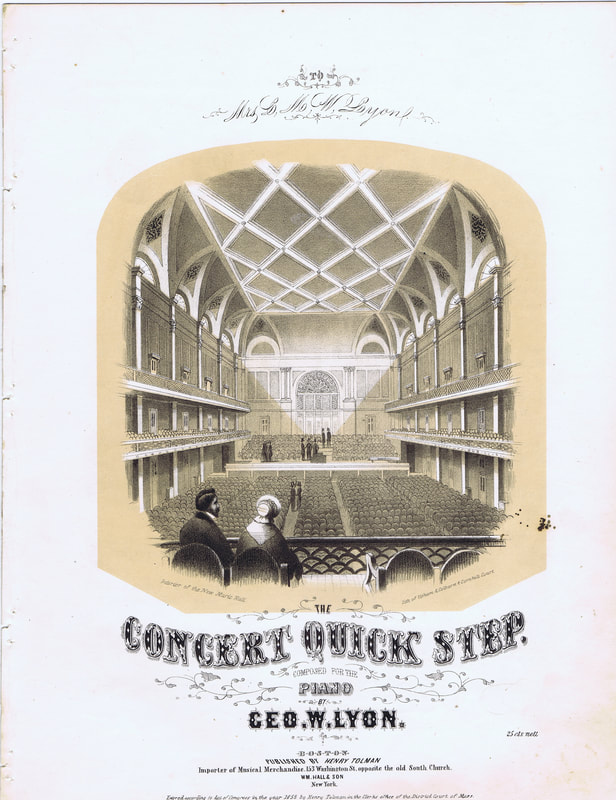

1853 - Boston Music Hall, interior view, litho by Upham and Colburn, Boston

|

There are many great examples of non-illustrated music in American publications that date from the earliest years (1780’s and 1790’s) to the Civil War and beyond. The vast majority of the presidential pieces prior to 1840 were done without pictorial illustrations and most of the other political issues of that time as well. The earliest U.S. sheet music folios were compositions for harpsichord and piano. Our first sonatas and initial songs by an American composer were most all without illustrations on the title pages.

A very popular piece such as The Yellow Rose of Texas did not need to feature a yellow rose pic, and indeed does not. That did not keep the initial state of first edition (with the mysterious composer’s initials – J.K.) from selling for $1,500 at Swann’s some years back. The great allure was the historic match of song with state.

Many years ago, I was puzzled by the Helen Maria Waltz. The title page had a simplistic lithographic drawing of some couples dancing, nothing eye catching. It was dedicated to a certain Mr. Fiske. Upon further exploration it was revealed that he was a marine merchant who was significant in assisting Irish emigres. The Helen Maria was a bark of his that brought many Irish to America. Knowing this changed how you looked at the piece and to some eyes also changed the worth.

There are literally thousands of cases where a music sheet of historical importance additionally features an attractive pictorially illustrated front, most always lithographed rather than engraved after 1830. And these bring additional interest, of course.

If the pictorially lithographed title-page was drawn by a known artist, especially someone famous, artistic merit as a marker for worth suddenly picks up historical relevance as well. It’s the same with a nice litho of a building, well executed. If it’s apparent that building is Pike’s Opera House in Cincinnati then historical allure adds to worth.

Of the collections in U.S. archives I know of, there was one that was begun as early as 1880. The collector, Robert Cushman Butler, cousin of famed actress Charlotte Cushman, may have been the first serious U.S. collector to prize the title-page illustrations above all else. Of the more than 800 music covers he left to us, now in Special Collections at Washington State University, maybe three or four are complete with music. The others are ‘cover only’, as the phrase goes, lacking musical notation.

The collection is astounding, not just for the rarities, but because Robert only wanted ‘early run’ pressings in high grade. Both black and white lithography and color lithography, as well as hand colored plates, are represented. They are truly staggering, seen in total, at one sitting.

A very popular piece such as The Yellow Rose of Texas did not need to feature a yellow rose pic, and indeed does not. That did not keep the initial state of first edition (with the mysterious composer’s initials – J.K.) from selling for $1,500 at Swann’s some years back. The great allure was the historic match of song with state.

Many years ago, I was puzzled by the Helen Maria Waltz. The title page had a simplistic lithographic drawing of some couples dancing, nothing eye catching. It was dedicated to a certain Mr. Fiske. Upon further exploration it was revealed that he was a marine merchant who was significant in assisting Irish emigres. The Helen Maria was a bark of his that brought many Irish to America. Knowing this changed how you looked at the piece and to some eyes also changed the worth.

There are literally thousands of cases where a music sheet of historical importance additionally features an attractive pictorially illustrated front, most always lithographed rather than engraved after 1830. And these bring additional interest, of course.

If the pictorially lithographed title-page was drawn by a known artist, especially someone famous, artistic merit as a marker for worth suddenly picks up historical relevance as well. It’s the same with a nice litho of a building, well executed. If it’s apparent that building is Pike’s Opera House in Cincinnati then historical allure adds to worth.

Of the collections in U.S. archives I know of, there was one that was begun as early as 1880. The collector, Robert Cushman Butler, cousin of famed actress Charlotte Cushman, may have been the first serious U.S. collector to prize the title-page illustrations above all else. Of the more than 800 music covers he left to us, now in Special Collections at Washington State University, maybe three or four are complete with music. The others are ‘cover only’, as the phrase goes, lacking musical notation.

The collection is astounding, not just for the rarities, but because Robert only wanted ‘early run’ pressings in high grade. Both black and white lithography and color lithography, as well as hand colored plates, are represented. They are truly staggering, seen in total, at one sitting.

|

1852 - early extravaganza, Frey litho for Sinclair, W.R. Beverly painter for set

|

3. Prominence

How was prominence determined and what factors were involved? By 1941, when Harry Dichter and Elliott Shapiro published their important work Early American Sheet Music: It’s Lure and Lore, a strong sense of prominence had already been established. It was clear among the top collectors, and no doubt among many curators as well, that historical relevance was the strongest draw and the greatest argument for conservation and archiving, if not also presentation and exhibitions. Still today, significance of connection to historical events brings the greatest interest in the popular sheet music collecting field. |

Secondly, artistic merit in design, that which struck Robert Butler, came to be seen as very important in illuminating American manners, moods and mores, as well as her important leaders and significant events. Artists like Winslow Homer and marine painter Fitz Henry Lane worked on music title-page design when they were young. The satirist D.C. Johnston did excellent work, as did the Philadelphia deaf artist Albert Newsam and Eliphalet Brown, Jr. who accompanied The Perry Expedition to Japan in 1852. There were many others that made their mark in music title-page design.

Thirdly, fame in composer and composition was on occasion the dominant factor in interest. Stephen Foster would be an excellent example here. Henry Work, the Civil War composer, was another. And there are examples of individual compositions that generated great fame, such as Julia Ward Howe’s lyrics for Battle Hymn of the Republic. There were also composers whose fame in classical composition crossed over into the popular sheet music field, such as Niccolo Paganini and Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

The overarching appeal was published music as social/cultural anthropology. You couldn’t find two better art forms linking together than the iconic images of lithographic art and the many evocative and diverse states of popular music composition. Together they told the amazing story of a nation that was in its first century of development and exploration.

Thirdly, fame in composer and composition was on occasion the dominant factor in interest. Stephen Foster would be an excellent example here. Henry Work, the Civil War composer, was another. And there are examples of individual compositions that generated great fame, such as Julia Ward Howe’s lyrics for Battle Hymn of the Republic. There were also composers whose fame in classical composition crossed over into the popular sheet music field, such as Niccolo Paganini and Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

The overarching appeal was published music as social/cultural anthropology. You couldn’t find two better art forms linking together than the iconic images of lithographic art and the many evocative and diverse states of popular music composition. Together they told the amazing story of a nation that was in its first century of development and exploration.